Looking at the Past and Present this AAPI Heritage Month

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) comprise roughly 6% of the United States population, and 28% of new immigrants. Over the last decade, both of these statistics have climbed as more people of Asian descent call America home. While a relatively small part of the population, AAPI have a long and storied history in America, playing pivotal roles in American and world history.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter issued proclamation 4650 commemorating the first 10 days of May as Asian/Pacific-American Heritage Week. This changed in 1990, when President George H.W. Bush expanded Asian/Pacific-American Heritage Week into an entire month-long celebration. Since then, every president has annually proclaimed May as Asian American and Pacific Islander Month, celebrating the diverse background and cultures of all AAPI, along with the crucial part they have played in American history.

However, this year’s AAPI Heritage Month will be quite different from those of previous years. Due to fear mongering and racism around the Coronavirus pandemic – using Asian people (specifically those of Chinese descent) as scapegoats for the virus’ prevalence – the rates of AAPI hate crimes skyrocketed during 2020 and into 2021. While the current rise in hate crimes can be explained, it does not exist in a vacuum. Peering into the recent history of America, one will find a long tradition of anti-Asian sentiment going back hundreds of years, directly influencing modern notions and stereotypes which AAPI are still defined by.

This AAPI Heritage Month is a critical point to look at Asian American history, analyzing the achievements AAPI have had and the hardships they have overcome. Learn more about that history, and find direct ways to help AAPI communities and people across the country.

A History of Discrimination

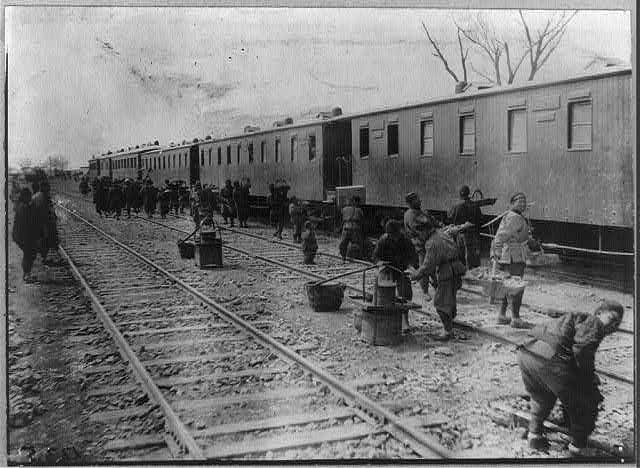

For hundreds of years, Asian and Pacific Islander sailors have found their way to American shores. However, around 1850 marked the first large-scale immigration of Asian people and Pacific Islanders, with the California Gold Rush drawing thousands to the West Coast. By the end of the 1850’s, Chinese immigrants made up a fourth of mining counties across the West, and were an essential workforce in building the transcontinental railroad. Yet, most Asians and Pacific Islanders who found their way to America were met with swift and harsh discrimination, setting a lasting precedent of AAPI as second-class citizens.

Most gold miners and railroad men were immigrants, but those of European ancestry were uniformly better treated and better paid. California’s Foreign Miners Tax required all foreign miners to pay $20 (about $500 adjusted for inflation) monthly to their employing mine. However, this tax was only really enforced against Latin American and Asian workers, with White immigrants rarely forced to pay. This bill set off a domino effect of legislative discrimination against AAPI which would remain prevalent for nearly a century.

After many anti-Chinese bills and laws, discrimination came to a head with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, barring the immigration of Chinese laborers. This law directly shrunk the Chinese workforce, and created hostility toward Chinese and other Asian Americans, forcing many AAPI to flee the country for their own safety. For nearly a century, Asian people and Pacific Islanders had very few opportunities for immigration or success in America, being strictly limited on the amount of immigrants allowed from Asian countries (especially China). It was not until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that America lifted its harsh limitations on Asian immigration, finally giving millions of Asians and Pacific Islanders the opportunity to call America home.

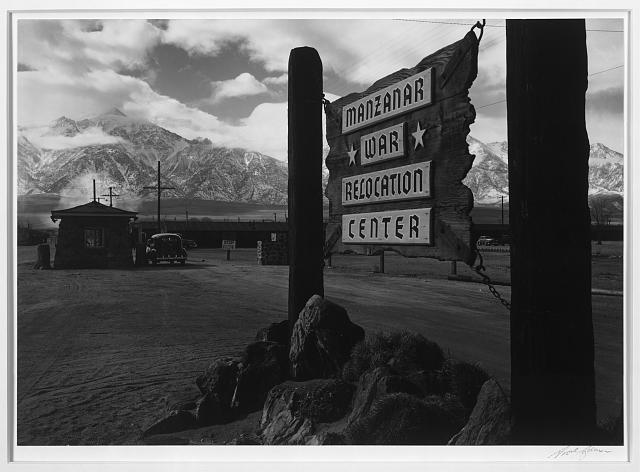

While much of 19th and early 20th century anti-AAPI sentiment is remembered as specifically targeting those of Chinese descent, that time was rife with discrimination for people from all over the Asian continent and the Islands dotting the Pacific Ocean. One notorious point of discrimination is 1942’s wartime Executive Order 9066: the forced relocation of 117,000 Americans of Japanese decent into federal internment camps.

The Japanese internment camps stand as an underacknowledged dark time in American history, when thousands of people of Japanese descent – most of them legally recognized citizens – were forced to give up their livelihoods and possessions, and were held captive by their own government. Although in 1988 President Ronald Reagan formally apologized for the internment camps and mandated the government pay all remaining survivors $20,000, the trauma and damages caused by internment can never be fully mended nor taken back.

Although the latter half of the 20th century was not marked by the same blatant anti-AAPI racism as the first half, the last 60 years contain numerous examples of AAPI discrimination and hate. In 1982, the high-profile murder of Vincent Chin sparked national outrage as his killers were sentenced to no jail time, serving as a turning point for Asian American Civil Rights.

Media has consistently discriminated against Asian Americans as well, with Hollywood enforcing harmful and offensive stereotypes along with casting White actors to portray Asian people and their stories.

The rise in discrimination in the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic can be traced to derogatorily calling the virus “China virus” and “Kung Flu,” but the hatred which AAPI have had to face has been codified by decades of overt and subtle racism and discrimination. First by law, then action and media portrayal, there is a storied history of Asian Americans being presented as second-class citizens, which Americans have absorbed through cultural osmosis. Thus, when COVID-19 was linked to Chinese people – and by extension, those who could be perceived as Chinese – many found a scapegoat upon which to focus their confusion, rage and panic.

Hate in the Age of Covid

The discrimination and constant othering of AAPI has been a static feature of life in America for many Asian Americans. However, in the wake of rising hate crimes, it seems many AAPI are having honest, out loud discussions about discrimination for the first time. As medical student and activist Natty Jumreornvong puts it, “It’s still all new to me, activism, and I think that’s what a lot of Asian Americans are starting to feel too…. We’re not really taught to speak out.”

Often, Asian Americans have been stereotyped as quiet and out of sight. While attempting not to overlook the decades of activism of AAPI have engaged in, many see the present moment as a time to reflect on how Asian Americans may have internalized the stereotypes which are used to define them. “The kinds of conversations we’re having now were unthinkable even two years ago … getting at questions of being perpetual foreigners, being told you speak English well,” said Manjusha Kulkarni, executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council and co-founder of Stop AAPI Hate. While AAPI have always been aware of their social status, recent events have many reanalyzing how they see themselves as both people of Asian descent as well as Americans.

Much of this lack of conversation comes from the exclusion of AAPI from discussions of race, placing them in a perpetual othered space. As PBS NewsHour reporter Stephanie Sy puts it in an interview with author Kim Tran, “In general, I feel like conversations about race don’t involve Asian Americans. It seems like a very White and Black conversation.” The exclusion from race-based conversation is often performed – intentionally or not – to place a wedge between AAPI and other ethnic minorities around the country, especially Black Americans.

University of California, Irvine professor Claire Jean Kim puts these discussions in context; “During World War II, the media created the idea that the Japanese were rising up out of the ashes [after being held in incarceration camps] and proving that they had the right cultural stuff … And it was immediately a reflection on black people: Now why weren’t black people making it, but Asians were?” This comparison is used insidiously to deny the realities of systemic racism, using Asian American success as proof that racism is cultural and not institutional.

This phenomenon has often been dubbed the model minority myth, arguing that AAPI have “made it” due to strong familial bonds and work ethic. However, Robert G. Lee in his essay The Cold War Origins of the Model Minority Myth outlines the real story behind the model minority myth; “The elevation of Asian Americans to model minority has less to do with the actual success of Asian Americans than to the perceived failure – or worse, refusal – of African Americans to assimilate.”

Despite decades of being held up as a standard for ‘good minorities,” this praise was always surface level, and used to discredit the prevalence of racist systems in America. However, once Coronavirus sent the country into a panic and Asian Americans were scapegoated as the cause of the virus, the notion of model minority fell to the wayside with a 21st century revival of “yellow peril.”

It is important to note that with the rise in hate crime there has emerged a counter movement disgusted by AAPI discrimination, with many Americans feeling a need to do something to support Asian American communities. Earlier this year, thousands marched across the country to demand justice for victims of hate crimes, and millions of dollars have been donated to pro-AAPI causes by individuals and massive companies alike. So if you feel the need to take a stand against AAPI hate, where’s the best place to start?

How You Can Help

In a time filled with discrimination, silence in the face of hate is complacency. As South African cleric and human rights activist Desmond Tutu once said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” To fully address discrimination and hate in our culture, we must all stand in solidarity against it, supporting those affected while demanding change. However, what are the steps to becoming a proactive ally?

The first thing to know is what to do if you see or experience hate crimes or discrimination in your everyday life. No one ever wants to experience or witness racial harassment, but it is important to know how to be an informed and effective bystander. There are many ways to safely assist victims during a hate incident, so take some time to learn how you can help. In that same vein, everyone should know how to report a hate crime locally. Hate crimes are historically under-reported, so it is crucial to help victims report crimes, ensuring that perpetrators are held accountable for their heinous actions.

In the event that you experience or witness an AAPI hate crime, it is important to support organizations assisting AAPI communities across the nation. Foundations like Asian Americans Advancing Justice are crucial for getting hate crime survivors the help, justice and protection they need. Similarly, Stop AAPI Hate and #HATEISAVIRUS are working tirelessly to curb the tides of racism, while guaranteeing Asian Americans are granted equal rights in all spaces. These organizations are nonprofits, meaning they rely on the generous donations of others to continue doing their necessary work. If you have the ability to give, these organizations are all fantastic ways to support AAPI communities while demanding justice.

As Americans, we must all use our voices to influence our government to take a stand against Asian American discrimination. The Biden Administration has already laid out its plan to address national hate crime rates, however more can still be done. Tell your representatives to approve legislation aimed at protecting AAPI, while better addressing and cataloging all hate crimes – not just those targeting AAPI.

It is normal to feel overwhelmed and powerless in the face of horrible violence and discrimination. Yet, we can always curb the tides of hate and give support to those in need. While Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month is a time to learn about the history of AAPI and how they add to the American experience, it is also a crucial time to reflect on what is happening right now, asking ourselves how we can help each other create a more accepting, respecting and nurturing country for the future.

Creating A Better Future

The panic and anger that the Coronavirus created has brought out an ugly side of many, intensifying the discrimination Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have faced in America for centuries. Despite the often repeated model minority myth, Asian Americans have consistently faced an uphill climb for acceptance and equality in America. Unfortunately, it took a rise in pandemic-fueled hate crimes to finally open serious discussions around what AAPI have faced and currently face as Americans citizens.

As vaccines roll out and businesses reopen, a return to normalcy is appearing on the horizon. However, we must all make certain that injustices done against AAPI are not forgotten, and that we grow as a country. With America’s history of Asian discrimination unearthed once again, now is the time to reflect and create more accepting spaces for AAPI.

If you’re interested in more ways you can help AAPI communities and people, check out Impactree’s AAPI Justice Action Hub.